BlackSuit ransomware: 8 years, 6 names, 1 cybercrime syndicate

It’s been nearly 20 years since ransomware became a significant threat, and some of today’s most prolific modern threats are the great, great, great-grandchildren of the original notorious strains. This is true in the case of BlackSuit ransomware, an operation identified as the fifth most dangerous threat to the U.S. public healthcare sector just six months ago.

A slow start?

BlackSuit is a private ransomware operation with no known affiliates and does not operate as a ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS). It is an active and widespread threat now, but that was not the case in 2023. BlackSuit was first observed during the second quarter of 2023 but represented less than one-half of a percent of all ransomware attacks through the end of that year. This might make it look like BlackSuit wasn’t doing much for a while, but that is rarely the case with successful threat operations.

Organized threat actors never take a break, and the attacks that we see are only one part of their ‘business.’ Consider what goes into a ransomware operation:

- Ongoing code development to ensure their ransomware/malware is effective and difficult to detect

- Infrastructure development, like command-and-control servers (C2), payment systems, communication channels, leak sites, etc.

- Strategic design of tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) to conduct the most effective and damaging attacks

- Victim and target research so the group can focus on high-value targets

- Recruiting and training of members (or RaaS affiliates) to ensure the group is prepared to scale up operations

These are just a few of the things that are always happening in the background as threat actors improve their operations. Many things must be in place before a group can escalate its attacks. We aren’t sure what BlackSuit was doing in 2023, but their threat activity escalated quickly at the end of the year. By February 2024, BlackSuit was one of the most active ransomware threats.

How does BlackSuit work?

Let’s break down the BlackSuit chain of infection, starting with the initial access. Like many threat actors, BlackSuit uses phishing emails that contain malicious attachments or links that will start the infection process when opened. The infected attachments often use macros to execute the code, and the links may lead to malicious websites that conduct drive-by download attacks. The group also uses malvertising to redirect users to their attack sites.

Remote desktop protocol (RDP) is the second most common vector for initial access. Approximately 13.3% of BlackSuit attacks start here, often with stolen credentials that BlackSuit purchased from initial access brokers.

BlackSuit will also exploit public-facing applications that are misconfigured, unpatched, or otherwise vulnerable to attack.

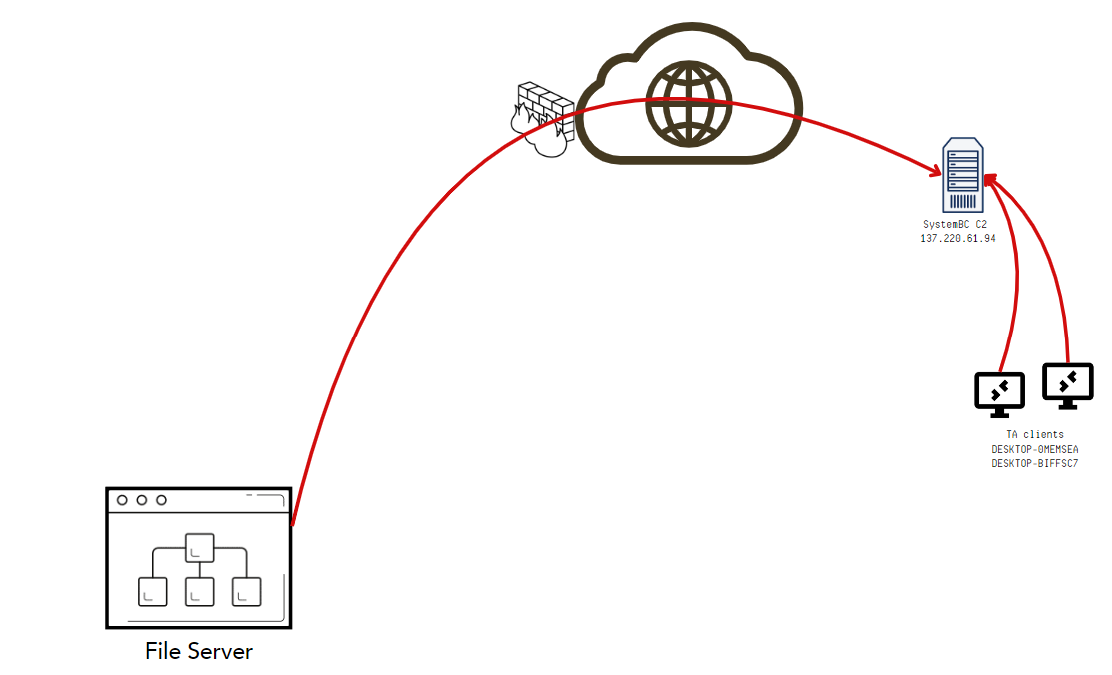

One of BlackSuit’s favorite tools is SystemBC, a remote access trojan (RAT) that allows threat actors to establish command-and-control (C2) capability through an anonymous proxy connection. The following is a simple illustration of this C2 connectivity:

We’re going to stick to a high-level overview, but you can see a full technical breakdown of a BlackSuit infection here.

Once BlackSuit has accessed a system, the threat actors attempt to establish persistence, escalate privileges, and begin lateral movement. Several tools are used for these operations:

- PowerShell: A cross-platform task automation suite initially released as a Microsoft Windows component in 2006. PowerShell’s capabilities allow threat actors to perform many types of malicious activities across the victim’s network. Microsoft’s PowerShell documentation is here, and here’s an article on how PowerShell is used in ransomware attacks.

- PSExec: Legitimate system software that lets you execute processes on other systems and fully interact with console applications without installing client software. Microsoft documentation for PSExec is here.

- Cobalt Strike: A commercial tool designed to simulate attacks and post-attack actions. See the MITRE ATT&CK page here for more on why threat actors use this software in their attacks.

- Mimikatz: A password stealer originally developed as a proof of concept to show Microsoft that its authentication protocols were vulnerable to an attack. Mimikatz can expose several vulnerabilities to steal passwords. You can find details here.

When ready, BlackSuit will begin data exfiltration so they can threaten to publish or sell the stolen data if the victim does not pay a ransom. They also delete volume shadow copies to interfere with recovery efforts and sometimes encrypt or delete the company backup files.

The next stage is the deployment of the ransomware payload. BlackSuit encrypts files across local and network drives using automated scripts or remote tools. The attackers usually obfuscate the name of the encryption executable by using something like “explorer.exe” or “abc123.exe.”

BlackSuit uses a partial encryption strategy, which makes the encryption process much faster. The idea is that partial encryption is less likely to trigger security alerts and will damage more files in less time.

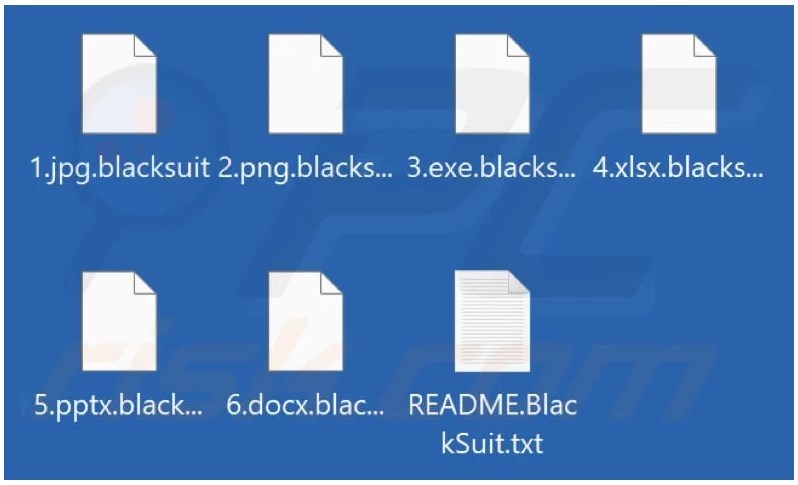

Encrypted files are renamed with a .blacksuit extension, and a ransom note named “README.BlackSuit.txt” is dropped on the desktop and in all folders with encrypted files.

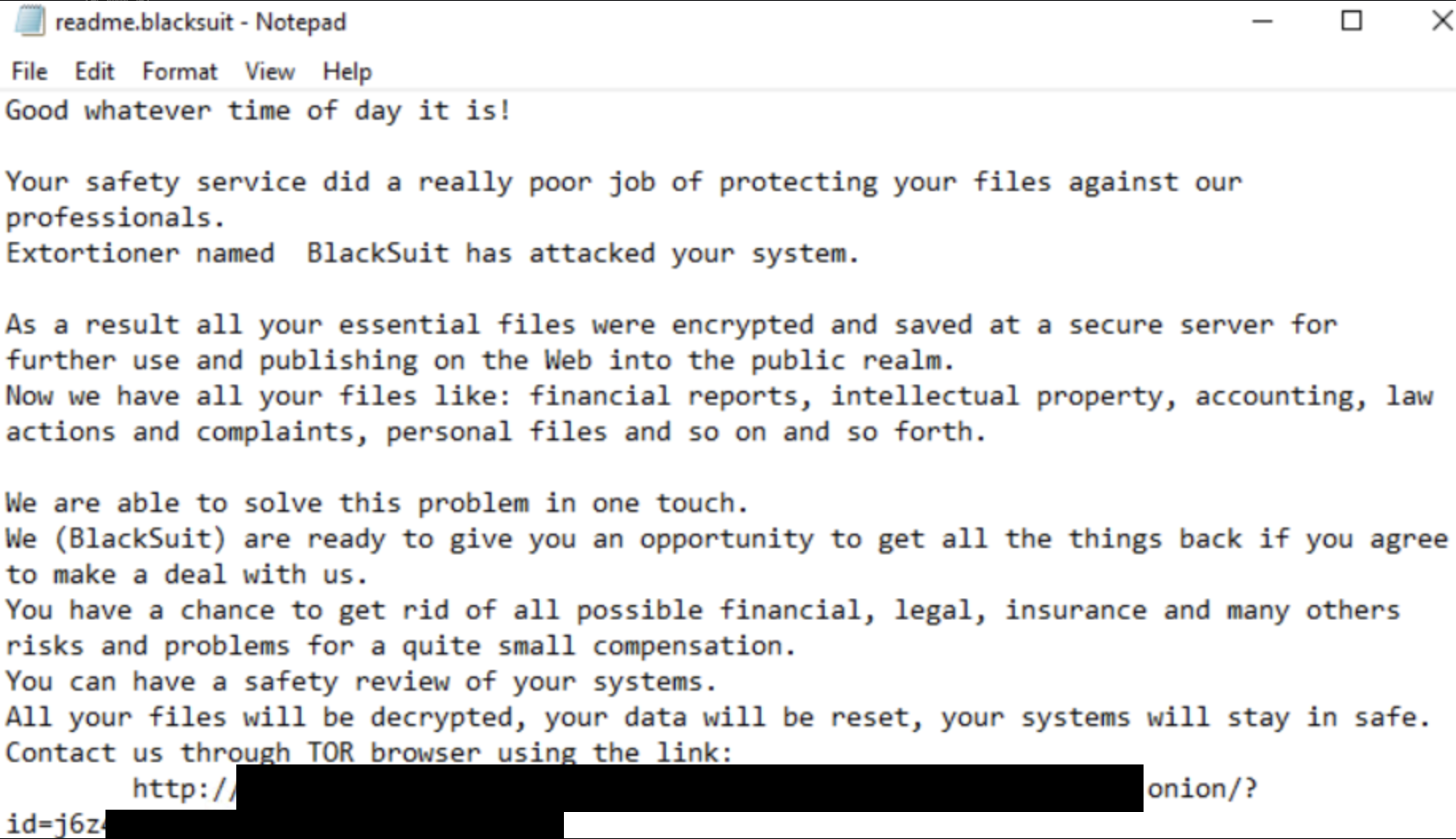

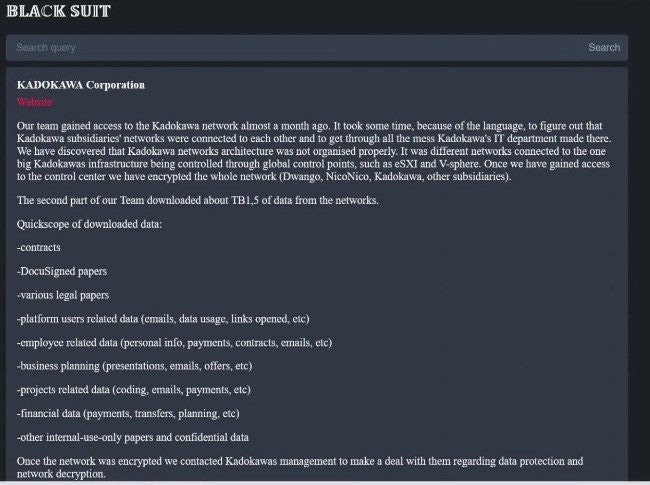

The ransom demand offers a decryption key and the privacy of your stolen files in exchange for a ransom — the typical double extortion threat. Meanwhile, the victim is listed on the BlackSuit shame/leak site.

BlackSuit targets both Windows and Linux systems. The Linux variant targets VMware ESXi servers and uses ESXi commands, Linux command line arguments, and other Linux-compatible tools to carry out the attack.

Notable victims

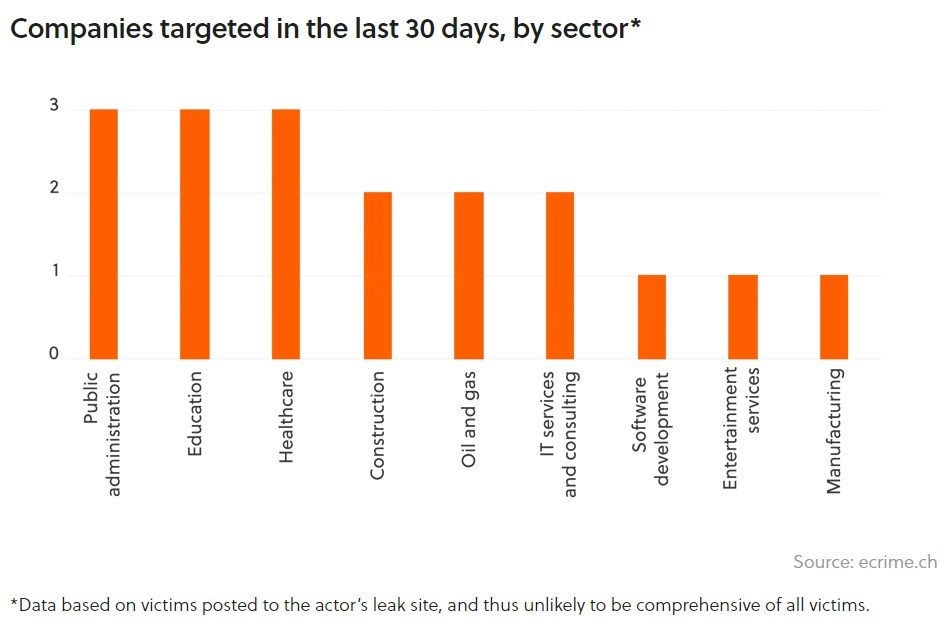

BlackSuit has targeted organizations across various sectors and countries. S-RM reports that most victims are U.S. companies, and 88% of them have been businesses with fewer than 1,000 employees.

BlackSuit’s big ransom haul came when they hit CDK Global, an American multinational company that provides dealer management systems and other software and services to approximately 15,000 auto dealerships across North America. Dealerships lost an estimated $1 billion in business disruptions and recovery costs.

An unidentified source told Bloomberg that CDK planned to pay the ransom, and a crypto-tracking firm observed a $25 million Bitcoin payment to an account controlled by BlackSuit. This is the third-largest ransomware payment observed or reported, behind Dark Angels/unnamed victim at $75 million and Phoenix/CNA Financial at $40 million.

In April 2024, the group also disrupted the operations of 160-plus blood plasma donation centers. This was an attack on Octapharma Plasma, which has operations in over 100 countries and donation centers across 35 states in the U.S. BlackSuit allegedly infiltrated Octapharma Plasma by targeting their ESXi systems with the Linux variant mentioned above.

BlackSuit has also disrupted ZooTampa, the Government of Brazil, Western Municipal Construction, and many more.

Lineage

BlackSuit didn’t just pop up out of nowhere. The name did, but the individual members of the crime syndicate have been around for many years.

Hermes ransomware burst on the scene in February 2016. The Hermes ransomware strain was considered ‘commodity ransomware’ because it was sold in underground forums where it was purchased for use by many other threat actors. It later transitioned into a ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) offering before tapering off in 2018.

Ryuk ransomware appeared in August 2018, and researchers quickly linked Ryuk to Hermes through code similarities. The Ryuk operation created a more sophisticated and destructive strain and may have been the first to conduct big game hunting attacks. Ryuk was often deployed after other malware like TrickBot, which made it part of a larger and more destructive attack chain.

To this point, the origins of Hermes and Ryuk were not clear. Some researchers suspected Hermes, and later Ryuk, were developed by the North Korean group Stardust Chollima (Lazarus Group, APT38). Others thought they were linked to a threat actor in Russia known as Wizard Spider (FIN12, UNC1878). Analysts eventually agreed that Hermes and Ryuk were of Russian origin.

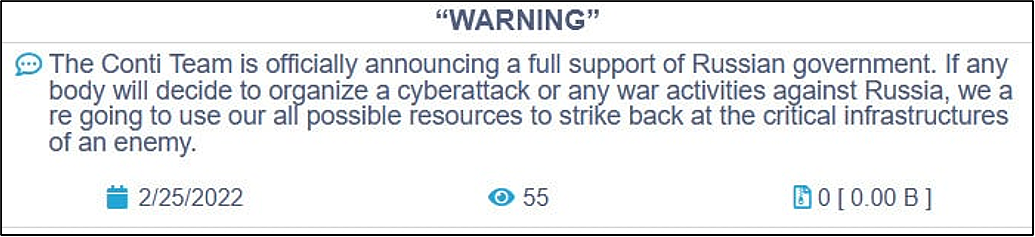

Conti ransomware emerged around December 2019, around the same time Ryuk started to go quiet. The two ransomware strains have been linked through code and infrastructure similarities, as well as evidence linking specific Conti members to Ryuk addresses. Conti operated as a RaaS and was collecting a lot of high-dollar ransoms until the leaders publicly announced support for the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

A Ukrainian researcher with access to Conti resources responded by sending sensitive Conti information to the media and posting private communications on X (formerly Twitter). He also published the source code for the Conti ransomware malware files.

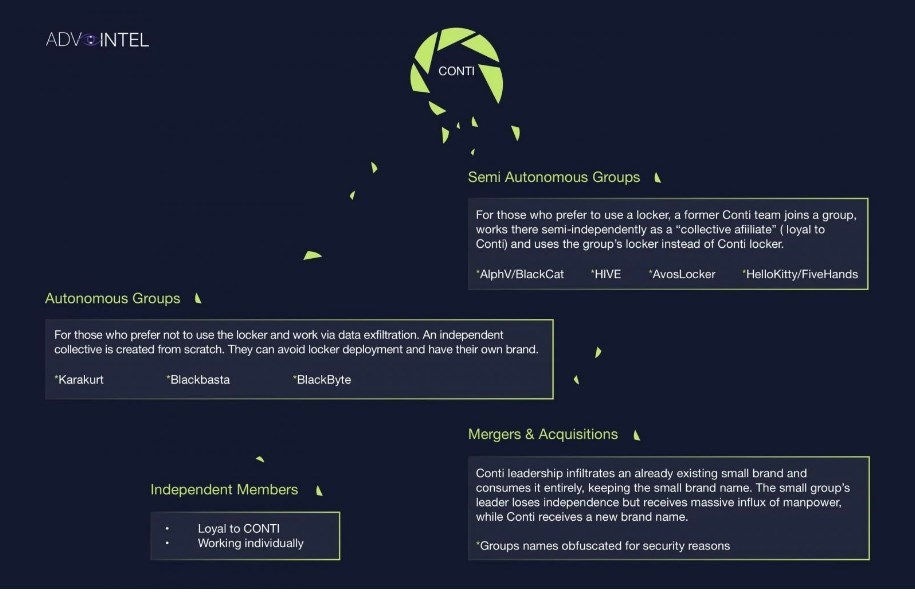

The damage was severe enough to destroy the Conti brand, and the members strategically dispersed across several new and existing groups in the ransomware ecosystem.

It may be through the ‘mergers & acquisitions’ bucket illustrated above that Conti members end up with the Zeon ransomware group, which was first observed in January 2022. Zeon started as an unsophisticated, commodity-level ransomware strain. The group soon rebranded to Royal ransomware and adopted more advanced Conti-like operations. Royal stopped its attacks in July 2023 after its high-profile attack on the City of Dallas. At this point, Royal rebranded to BlackSuit. Researchers speculate this rebrand was to avoid law enforcement and make their operation more attractive to potential affiliates.

BlackSuit today

Before fading out, the Royal ransomware group began experimenting with a new encryptor called BlackSuit. This led many industry analysts to correctly predict that Royal was planning a rebrand to BlackSuit. In June 2023, less than a month after BlackSuit emerged, researchers found the two strains to be ‘nearly identical.’ For this reason, many researchers will refer to BlackSuit and Royal ransomware as a single entity. For example, experts attribute over 350 attacks and $275 million in ransom demands to BlackSuit since 2022, even though BlackSuit wasn’t the name of the group until 2023.

Despite the similarities, the BlackSuit operators do some things differently:

- The malware uses enhanced partial encryption and improved evasion techniques, and the developers have added more data exfiltration options, like RClone and Brute Ratel.

- The attackers demand higher ransom amounts, usually from $1 million to $10 million. They are also more aggressive in collecting the ransom, contacting their victims by phone or email to bully them into paying.

- BlackSuit has expanded its targeting capabilities by adding IP verification abilities and arguments to specify target directories.

BlackSuit is a current threat, with dozens of new victims posted to its leak site in the last few weeks. You can defend against this threat by starting with the basics:

- Make sure you have strong email security and phishing awareness. Phishing is the primary vector for BlackSuit intrusion.

- Enforce multifactor authentication and least privileged access. This will make it more difficult for attackers to log in with stolen credentials, and it will restrict what the intruder can discover.

- Keep systems and applications updated. BlackSuit exploits software, firmware, and operating system vulnerabilities.

- Segment your network to restrict lateral movement in case of a breach. This will ‘reduce the blast radius’ and contain the potential damage to smaller sections.

- Use extended endpoint detection, continuous network monitoring, and automated incident response. This will identify and disrupt suspicious activities in real-time.

- Keep secure and offline backups of critical data and regularly test them to ensure they work as expected.

- Disable remote desktop protocol (RDP) if possible since it is the second-highest intrusion point for BlackSuit ransomware.

There’s no reason to be a victim of BlackSuit or any other ransomware. Protect your credentials, secure your applications, and maintain a good backup system that protects all critical data. Take advantage of free resources like Stop Ransomware, and give us a call so we can help you defend every threat vector from ransomware attacks.

Barracuda can help

Barracuda provides a comprehensive cybersecurity platform that that defends organizations from all major attack vectors that are present in today’s complex threats. Barracuda offers best value, feature-rich, one-stop solutions that protect against a wide range of threat vectors and are backed up by complete, award-winning customer service. Because you are working with one vendor, you benefit from reduced complexity, increased effectiveness, and lower total cost of ownership. Hundreds of thousands of customers worldwide count on Barracuda to protect their email, networks, applications, and data.

Subscribe to the Barracuda Blog.

Sign up to receive threat spotlights, industry commentary, and more.