What are democratic transitions and why are they needed?

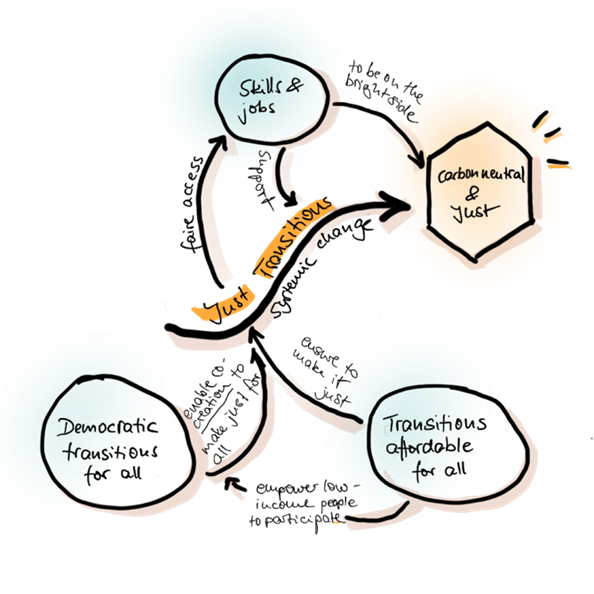

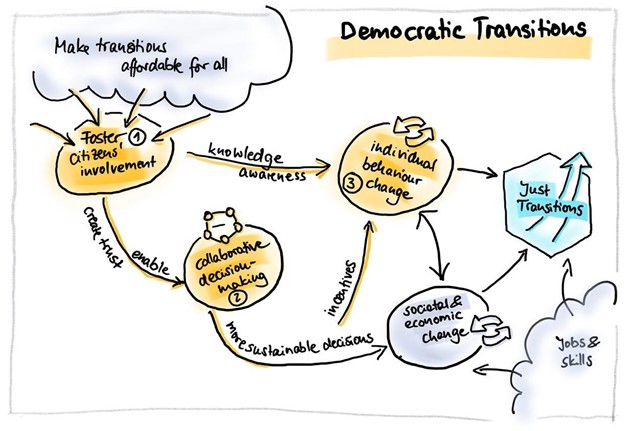

Tackling climate change requires deep systemic change in society (European Environment Agency 2019). These changes will affect all stakeholders and population groups – some will benefit from new business ventures and jobs; to others it will pose the risk of energy poverty, unemployment, health problems and other burdens. Hence, their active involvement in policy-making and implementation is essential to ensure the burden of progressing towards carbon neutrality, a goal that will benefit all groups of the society equally, is also shared by all fairly. Urban Sustainability and effective climate action at the appropriate scale will therefore not be possible without bringing all citizens on the journey (EEA, 2021). Policy and action on climate change should be approached as intertwined with action towards social and environmental justice, because environmental inequality and unequal exposure to impacts of climate change leads to social inequalities. Co-created climate actions involving different citizen groups in appropriate ways have high chances to be also “just” in nature. Hence if “justice” is not considered in designing new green infrastructure for example, it can exacerbate existing inequalities, create new ones or even preserve an inequal status quo. (Zacharzewski and O’Phelan 2022).

The New Leipzig Charter calls for an integrated approach to urban development that requires the involvement of the general public as well as social, economic and other stakeholders in order to consider their concerns and knowledge. The idea is that the engagement of all urban actors will strengthen local democracy. According to Anthony Zacharzewski, President & Director-General at Democratic Society, “There are democratic decisions that aren't just, but you can't really have just decisions that aren't democratic.” (Zacharzewski and O’Phelan 2022).

This report emphasises on the need indicated above to involve citizens actively and broadly in Transitions towards a carbon-neutral and climate-resilient Europe in order to make these transitions just. It concentrates explicitly on citizen engagement and involvement as a key element of Just Transitions processes. While it will be embedded in a wider stakeholder participation process including various other organisations in the form of partnerships, this particular focus is also motivated by the fact that there can be partnership without participation but not participation without partnership (Adams and Ramsden 2019).

For the purpose of this study, we understand that:

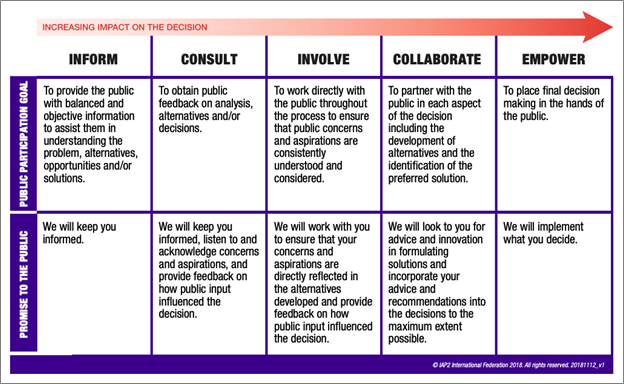

Transitions are democratic, if all groups of citizens are able to access information equally and are empowered to be heard, to listen to others’ needs and wants, and to co-create and co-design actions towards a carbon-neutral and climate-resilient Europe.

Why are cities important?

Cities and towns are the places where most people in Europe live. It is in cities and towns that the impacts of climate change and the Transitions towards carbon neutrality will be most experienced. Additionally, city residents’ behavioural patterns will have a significant impact in Europe's future and will determine the level of implementation of the Green Deal in practice. Cities are the places where the EU, national, regional, and local policies are implemented and where Just Transitions are made possible. A multi-level governance approach is therefore needed to connect city residents to the national and European level. Under the new Cohesion Policy objectives, cities have a central role. For example, under the Policy Objective 1 ‘Smarter Europe’, the Policy Objective 2 ‘Greener Europe’, and since local governments are closest to citizens, also under the Objective 5 ‘Europe closer to citizens by fostering the sustainable and integrated development of all types of territories’ (European Commission n.d.). With more than 10,000 local authorities having signed the Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy, cities are also in the lead in climate action.

On the other hand, cities also combine high concentration of multiple vulnerabilities to the climate phenomena. With the potential to implement radical local experiments that can be tested, upscaled and improved, therefore contributing to effective socio-ecological transitions is not only possible, but also desirable for cities. They operate as a place for innovation, co-creation and participatory citizen-led actions, using technology and space (European Commission-Joint Research, n.d.). As the New Leipzig Charter underlines, cities can act as “laboratories for new forms of problem-solving and test beds for social innovation”(EU 2020). Hence, cities can lead the way on how to engage citizens and become role models.