There was a time when the world appeared boundless and inexhaustible. We are just beginning to realize that it is both limited and surprisingly vulnerable. It follows that if we are to survive at all as a species, we shall have to learn to see the world in a different light. Warnings have been sounded. Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO, opened the international Biodiversity Science Policy Conference held at UNESCO Headquarters earlier this year by underlining that preserving biological diversity represents ‘as big a global challenge as climate change’.

We already know that our planetary sweet water supply is threatened by pollution, but also by climate change, since even the colossal glaciers of the Himalayas, which feed the major rivers of Asia and provide water to billions in China, India and South-East Asia, have begun to shrink at an alarming rate.

Our great forests are threatened, too, both by greed and by the simple survival needs of a growing population. And while all this looks stark, frameworks do exist through which to address the threat and begin the work. One of these is the World Heritage Convention.

In its thirty-eight years of existence, the World Heritage Convention has developed a worldwide network of 890 sites, which may be regarded as so many carefully watched monitors that centralize observations touching upon climate, biodiversity, threatened species and kindred issues. Nor is the World Heritage Convention working at this alone. It is doing so in close coordination with such other great organizations and networks as the Convention on Biological Diversity, Conservation International, International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, United Nations Environment Programme – World Conservation Monitoring Centre, World Bank, NatureServe, Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals and many others.

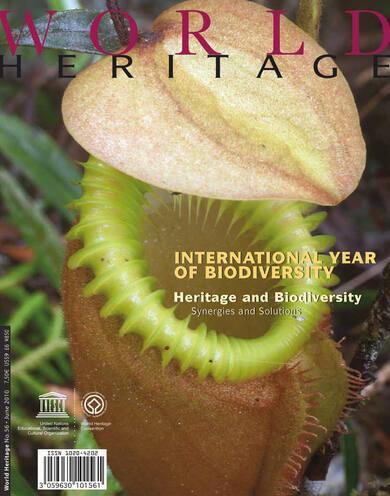

This issue of World Heritage, published on the occasion of the United Nations International Year of Biodiversity (2010) highlights the work done by these remarkable organizations, both on their own and in cooperation with the World Heritage Centre to address these burning issues.

Table of Contents

Synergies between World Heritage sites and Key Biodiversity Areas

The interests of the World Heritage Convention are convergent with those of the biodiversity conservation community.

Marine World Heritage: the time is now. Protecting the “best of the best” in the ocean

Since 2005, the mission of the World Heritage Marine Programme has been to safeguard the world’s most outstanding marine sites, to make sure they will be preserved and allowed to thrive for generations to come.

Climate change and a natural solution

In 2005, at its 29th session, the World Heritage Committee acknowledged the potential effect of climate change on World Heritage sites.

Cultural diversity, biodiversity and World Heritage sites – a tribute to the flexibility of the World Heritage system.

The Convention recognizes the interconnectivity of biological and cultural diversity in identifying and conserving the rich biodiversity of World Heritage sites.

Western Ghats: biodiversity, endemism and conservation

This biodiversity hotspot is home to a rich endemic assemblage of plants and species and has to face tremendous population pressure.

Kew Gardens and the conservation of biodiversity – from a royal garden to a global botanic resource

Since the 18th century, the Botanic Gardens of Kew made a significant and uninterrupted contribution to the study of plant diversity and economic botany.

Funding for biodiversity: implications for Word Heritage sites

Protected areas, including World Heritage sites, are the cornerstones of biodiversity conservation and adequate funding is an essential prerequisite for effective management of these prime assets.