Abstract

What can psychologists do to address social determinants of health and promote health equity among America’s approximately 20 million children of immigrant families (CIF)? This article identifies gaps in current research and argues for a stronger role for psychologists. Psychologists can advocate for and enact changes in institutional systems that contribute to inequities in social determinants of health and promote resources and services necessary for CIF to flourish. We consider systemic exclusionary and discriminatory barriers faced by CIF, including a heightened anti-immigrant political climate, continued threat of immigration enforcement, restricted access to the social safety net, and the disproportionate health, economic and educational burden of the COVID-19 pandemic. We highlight the potential role of psychologists in (a) leading prevention that addresses stressors such as poverty and trauma; (b) changing systems to mitigate risk factors for CIF; (c) expanding workforce development across multiple disciplines to better serve their needs; (d) identifying mechanisms, such racial profiling, that contribute to health inequity, and viewing them as public health harms; and (e) guiding advocacy for resources at local, state, and federal levels, including by linking discriminatory policies or practices with health inequity. A key recommendation to increase psychologists’ impact is for academic and professional institutions to strengthen relationships with policy makers to effectively convey these findings in spaces where decisions about policies and practices are made. We conclude that psychologists are well-positioned to promote systemic change across multiple societal levels and disciplines to improve the wellbeing of CIF and offer them a better future.

Keywords: Children in immigrant families, Mental health, Health equity, Multidisciplinary teams

With 44.8 million immigrants in the US as of 2018 and a projected doubling by 2065 (Budiman et al., 2020), children in immigrant families are a high priority group for receiving mental health supports. Children in immigrant families (CIF) – defined as those who are either foreign born or have at least one parent who is foreign born (Linton et al., 2019) – comprise 26% of the population below age 18 in the U.S., according to Migration Policy Institute estimates of the 2020 Current Population Survey (Batalova et al., 2021). Immigrant-origin children and youth (i.e., first generation) have often fled violence in their home countries and experienced additional traumas en route to and upon arrival in the US (Sangalang et al., 2019). Even second generation CIF require resources and supports to successfully integrate into US society (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2015).

The field of psychology has a weak track record of prioritizing health equity. The American Psychological Association (APA) recently acknowledged how the organization and discipline have contributed to systemic racism (American Psychological Association, 2021). For the most part, psychologists’ training, practice, and research has focused too narrowly on the individual, and does not include many of the mental health issues pertinent to CIF (Pineros-Leano et al., 2017) nor detail how psychologists can better address such needs. For instance, there is a need for intervention development and rigorous evaluation to build an evidence-base of trauma-informed, culturally responsive mental health programs and practices for immigrant children, children of immigrants, and their families (Pina et al., 2019; Zayas et al., 2017). Clinicians have requested guidance on how to support youth and families to prioritize their mental health when many of their basic needs (e.g., stable housing, sleep, employment, family) are not met (Zayas et al., 2017). When working with detention or deportation, providers need best-practices for post-release services, and information about services available in destinations that lack a well-established non-profit sector (Zayas et al., 2017). CIF are at risk for poor mental health outcomes given exposure to racism and discrimination (Shonkoff et al., 2021), family separation (Bouza et al., 2018), and negative school and social interactions (Enriquez, 2015). Services that fail to culturally adapt - considering geographic context, English proficiency, and immigration status - can lead to negative mental health outcomes (Pineros-Leano et al., 2017). In this article, we describe how psychologists can use research advances on structural inequities and focus on systems to improve life-course opportunities and supports for CIF.

Guiding Conceptual Framework

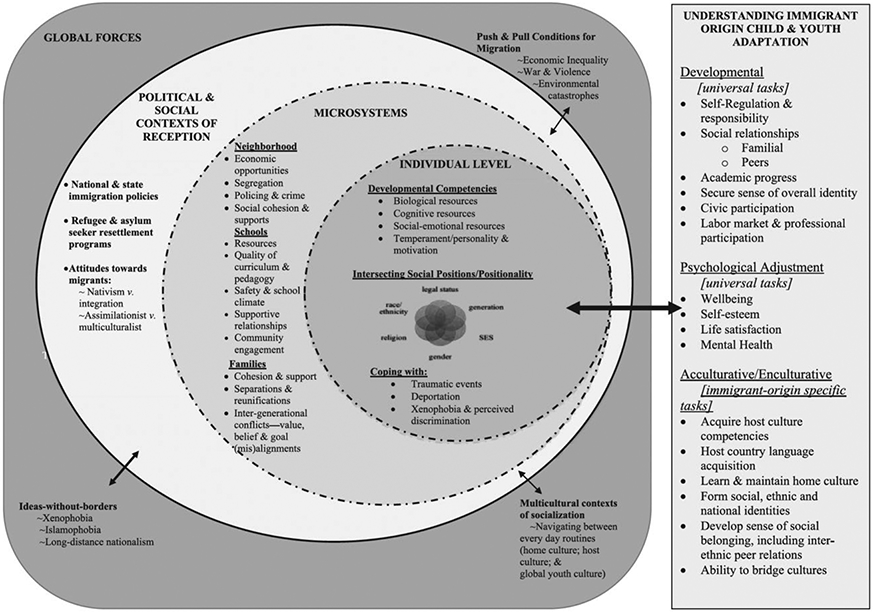

In February 2022, the American Psychological Association (APA) encouraged psychologists from all fields to ground their work in population health models, which they conceptualized as socio-ecological public health approaches to both promoting health and eliminating health inequities across populations. We use a socio-ecological model, Suarez-Orozco’s 2018 “Integrative risk and resilience model for understanding the adaptation of immigrant-origin children and youth” (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2018), to review systemic exclusionary and discriminatory barriers to health faced by CIF (see Figure 1). These include global forces such as racism; political and social contexts of origin and reception where national and state policies can restrict access to the social safety net; inequitable neighborhood micro-systems; and individual level factors requiring CIF to cope with traumatic or adverse events. For each socio-ecological level of Suarez-Orozco’s model, we identify challenges impacting the well-being of CIF that psychologists should address. We also argue that this framework should be used to identify specific institutional laws, policies, or practices that appear “neutral” on their face, but which have negative effects given vulnerability of undocumented parents, such as profiling in racialized traffic stops (Armenta, 2017; Garcia, 2019; Smith et al., 2021).

Figure 1. Integrative Risk and Resilience Model for Understanding the Adaptation of Immigrant-origin Children and Youth (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2018).

Note. From “An integrative risk and resilience model for understanding the adaptation of immigrant-origin children and youth” by C. Suárez-Orozco, F. Motti-Stefanidi, A. Marks, and D. Katsiaficas, 2018, The American Psychologist, 73(6), p. 781–796. Copyright 2018 by the American Psychological Association. Reprinted with permission.

Global Forces (e.g., Racism)

The 2015 National Academies report on the Integration of Immigrants into American Society found three areas of concern: lack of legal status impacting both US born and non-US born children; racial stratification of immigrants; and limited naturalization of these families. Work by Acevedo-Garcia, Joshi, Ruskin, Walters, & Sofer (2021) shows how the stratification by legal status has curtailed opportunities to benefit from social policy. The majority of children in immigrant families are U.S. citizens themselves, (16.7 out of 19.6 million; Child Trends, 2018). Yet, they face unique challenges due to parental or family member immigration status, such as social stigma, vulnerability, racism, and reduced access to safety net programs (Acevedo-Garcia, Joshi, Ruskin, Walters, Sofer, et al., 2021). Even with many assets, children of undocumented immigrants face adjustment and anxiety disorders, and the intergenerational transmission of economic disadvantage (Hainmueller et al., 2017). Research increasingly shows that legality is not a dichotomy between undocumented and legal status but a continuum (Acevedo-Garcia, Joshi, Ruskin, Walters, & Sofer, 2021). Acevedo-Garcia, Joshi, Ruskin, Walters, & Sofer (2021) define legality as “an axis of stratification that classifies immigrants into categories and assigns these categories different degrees of access to social policies and programs, which has health implications” (p.1101). Acevedo-Garcia, Joshi, Ruskin, Walters, Sofer, & Guevara (2021) use the example of 2-parent 2-child families with incomes of $25,000. Both parents must have social security numbers in order for the citizen/qualified immigrant children to receive any money from the Earned Income Tax Credit (otherwise a $5,980 benefit). In contrast, under the American Rescue Plan Act, the citizen/qualified immigrant children would receive the full Child Tax Credit ($6,600). Stratified access reflects the harmful assumptions that people with lawful immigration status or US citizens in mixed-status families are less deserving of basic needs and do not socially belong.

Research consistently shows that although undocumented immigrants are the ostensible target of immigration policy enforcement, the violence against them is de facto also directed to their families and communities, including legal immigrants and U.S. citizen members (Cervantes & Menjívar, 2020; Menjívar & Abrego, 2012). Undocumented status is associated with greater health risks, but adverse exposures exist, albeit at a lower level, among immigrants with higher legal status (Torres & Young, 2016). The health risks associated with illegality include psychosocial stressors such as fear of deportation, direct physical threats such as detention and family separation, and diminished access to health promoting resources (Asad & Clair, 2018; Cervantes & Menjívar, 2020). These factors are associated with child and youth mental health problems (Eskenazi et al., 2019; Roche et al., 2020).

Political and Social Contexts of Reception

The political context of reception plays a significant role in CIF’s mental health (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2018). Increased rates of encounters with US Customs and Border Patrol at the southern border in 2021 indicate greater new migrant arrivals to the Southwest area (US Customs and Border Protection, 2022). Many CIF arrive with significant trauma histories due to prolonged stays in dangerous parts of Mexico and Central America caused by policies like the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) (Mattingly II et al., 2020; Ornelas et al., 2020). MPP means that the U.S. Government reverts certain Mexican citizens and nationals of countries other than back to their countries while their asylum proceedings are pending (Homeland Security, 2021).

Strained relationships or encounters with professionals (e.g. teachers, childcare workers, police, and personnel of youth organizations) can negatively affect CIF (Smith et al., 2021). Smith and colleagues (2021) highlighted the detrimental effects of interactions during traffic stops in New York. Police officers’ racial profiling leads to “exploratory” stops of Latinx drivers solely as a pretext to ask about immigrant status (Armenta, 2017; Garcia, 2019). These experiences leave children with psychological difficulties due to the trauma and stress of these experiences (Enriquez, 2015; Menjívar & Cervantes, 2016; Smith et al., 2021). One study documented that an immigration raid led to markedly higher levels of stress and poorer health for the entire Latino community in the county in which that raid occurred (Lopez et al., 2017). Psychologists, working with sociologists, can document through research the extent of direct causal links between racially profiled traffic stops and harms done to CIF and their communities.

Stratification and targeting of immigrants along a continuum of legality has also been codified in U.S. social policy (Acevedo-Garcia, Joshi, Ruskin, Walters, & Sofer, 2021). The 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA), commonly known as “welfare reform,” stratified undocumented immigrants, legal immigrants and U.S. citizens in immigrant families along a continuum of legality and restricted access to anti-poverty programs. Many immigrant families lost access, contributing to their very high child poverty rates. (Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2022). These policies affect not only undocumented immigrants but also citizens living in mixed-status families, defined as those with at least one noncitizen member) or immigrants that do not have 5-years to qualify as residents.” (Acevedo, Joshi, Ruskin, Walters, Sofer, 2021). Although U.S. citizen children in families with undocumented members represent nearly one-fifth of all children in poverty, they do not have access to one of the major anti-poverty programs, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which excludes families where even one member does not have a social Security number. The CARES Act of 2020 required spouses and dependents to have a social security number, thus disqualifying millions of otherwise eligible CIF due to mixed immigration status of families (Gelatt et al., 2021).

Acevedo-Garcia and colleagues recommend that eligibility and benefit levels be determined by the developmental, health, and nutritional needs of each child, rather than family immigration status. More broadly, access to the safety net overall should be independent of immigration policy (Acevedo-Garcia, Joshi, Ruskin, Walters, Sofer, et al., 2021) and with minimized administrative burdens to access. The American Rescue Plan enabled citizen and lawfully present children to be eligible for the EITC, thus reducing child poverty (Acevedo-Garcia, Joshi, Ruskin, Walters, & Sofer, 2021). Making this permanent and returning to pre-2018 eligibility rules (including children without social security numbers) would enable more youth in immigrant families to have protection from poverty. Obtaining legal status and work authorization is critical. In an amicus brief for the 2019 DACA Supreme Court case (Department of Homeland Security et al v. Regents of the University of California et al), R. Smith and other scholars outline the benefits of DACA (Smith et al., 2019), citing a positive impact on intra-family mechanisms that promote upward mobility. DACA protects against the harms that US-citizen children would experience were a family member detained or deported.

Micro-systems (e.g., Healthcare, Education, Neighborhoods)

As shown in Figure 1, there are many commonalities in relation to mental health challenges, despite differences in immigration status (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2018). Accessing timely, culturally sensitive, and linguistically concordant mental health services remains exceedingly difficult, particularly for CIF who are un- or under-insured, or whose parents do not speak English (Pineros-Leano et al., 2017). Heightened anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies in the past several years have augmented CIF’s fear and stress (Ornelas et al., 2020; Patler & Pirtle, 2018; Roche et al., 2021) and increased hesitancy to access institutional supports (Mattingly II et al., 2020), including mental health services. Among youth who are eligible for safety net resources (e.g., food security, housing stability, parent training supports, or mental health services), many do not receive them due to confusion about eligibility and fear of jeopardizing their families (Yoshikawa et al., 2013). In one study, use of services declined for Latino mothers and children after the hostile immigration law SB1070 law was passed (Toomey et al., 2014). The decline was greater for the US-born than for the foreign-born mothers (Toomey et al., 2014).

Homeownership is one critical resource among immigrant families considering its importance for child development, community building, asset-building, and economic security. Homeownership, an indicator of immigrants’ assimilation and integration, has slowed because of a larger decrease in immigrants’ social mobility (Sánchez, 2018). Housing quality has also been linked to health and mental health outcomes. Using risk scores in the American Housing Survey, Chu and colleagues identified disparities in housing quality, with non-white immigrant households among those experiencing worse housing conditions (Chu et al., 2021). Through conducting evaluations that allow for causal inference, public health research teams including psychologists have contributed to the scientific understanding of the relationships between housing factors, health, and human development (Hernández & Swope, 2019). Psychologists can help conduct rigorous evaluations of housing interventions and policy, include immigrant families, and test the effects on mental health and equity outcomes (Hernández & Swope, 2019).

Immigrant communities have been among the hardest hit--physically and financially--by the COVID-19 pandemic. Many work in essential industries, at greater risk of virus exposure, with less access to social safety net services for temporary job or income loss (Kiester & Vasquez-Merino, 2021). Fuligni and Tsai (2015) report that during adolescent identity development, family continues to be a critical source of support and guidance. Yet such extreme hardships can challenge a family’s ability to offer youth a nurturing environment.

Individual-level Factors that Impact CIF

Suarez-Orozco’s model distinguishes between three types of individual-level tasks: developmental (e.g., self-regulation, social relationships); psychological adjustment (e.g., self-esteem, mental health) and acculturative/enculturative (e.g., host country language acquisition, forming social, ethnic, and national identities). The first two categories are labeled “universal tasks,” while the acculturative/enculturative tasks are immigrant-origin specific. They highlight many added tasks that CIF must navigate, that vary by individual positionality. Many immigrant and refugee youth have unique needs stemming from adverse childhood events in their native countries, the migration process, exposure to war, death of loved ones, family separation, and the stress of trying to adapt to the host culture (Burbage & Walker, 2018) where they may suffer racial discrimination (Asad & Clair, 2018). They also face social isolation and chronic stress related to family members’ citizenship status (Eskenazi et al., 2019; Torres & Young, 2016).

Opportunities for Psychologists to Practice the APA’s Four Principles of Population Health in the Context of Improving Conditions for CIF

A central feature of population health intervention is a multi-tiered approach for mental health prevention, where health promotion resources are available to everyone in a community (Tier 1), monitoring and screening is conducted to refer individuals with elevated risk factors (Tier 2), and clinical services are provided for severe or diagnosis-level health conditions (Tier 3) (American Psychological Association, 2022). Within this tiered approach, the APA designed the four principles of population health: 1. “Work within and across diverse systems”; 2. “Work"upstream" by promoting prevention and early intervention strategies”; 3. “Educate psychologists and community partners on population health”; and 4. “Enlist a diverse array of community partners.” Below we identify examples of opportunities for psychologists to practice these principles in the context of supporting CIF, with calls to action highlighted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Opportunities for Psychologists to Practice Principles of Population Health in the Context of Supporting Children from Immigrant Families

| Principle of population health |

Actions for psychology organizations (e.g., university departments, professional associations |

Example references from psychology and other fields |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Work within and across diverse systems | • Learn and practice structural competency | (Petty et al., 2017) (Hansen & Metzl, 2019) |

| • Work within systems such as schools, detention centers, early childhood care, community based organizations, etc. | (Herman et al., 2019) (O’Hara et al., 2019) (Turner et al., 2021) | |

| • Conduct equity impact assessments of social programs and policies, and advocate for policy reform | (Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2022) (Hardy et al., 2021) | |

| 2. Work upstream by promoting prevention and early intervention strategies | • Test and reform schools’ universal prevention and early intervention programs to be appropriate for children from immigrant families | (Burbage & Walker, 2018) (Ascenzi-Moreno & Seltzer, 2021) |

| • Develop and test early intervention health programs that are culturally and linguistically competent for immigrant children, children of immigrants, and their families, to fill gaps in the evidence-base | (Beehler et al., 2012) (McNeely et al, 2020) | |

| 3. Educate psychologists and community partners on population health | • Train and supervise community health workers to deliver culturally and linguistically competent prevention programs | (Ford-Paz et al., 2019)(Agarwal et al., 2019) |

| • Create multi-disciplinary teams to develop, evaluate, and implement best practices for CIF | (Ford-Paz et al., 2019) (Stein et al., 2002) | |

| 4. Enlist a diverse array of community partners | • Partner with community leaders (e.g., spiritual or religious) to identify community priorities and facilitate access to care | (Oppenheim et al., 2019) (Yamada et al., 2012) |

| • Build capacity to conduct Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) | (Boursaw et al., 2021) (Coombe et al., 2020) |

“Work Within and Across Diverse Systems”

The first population health principle, “Work within and across diverse systems” includes psychologists developing structural competency and learning from practice in non-clinical settings to better understand the needs of the community. Structural competency involves addressing how institutions, policies, and practices can create or exacerbate conditions that generate inequity and worsen American public health. To complement research and action, there are tailored resources and trainings for psychologists to develop structural competency, such as case-studies for mental health professionals (Hansen & Metzl, 2019). Structural competency should be integrated throughout learning, e.g., in all courses of a curriculum (Petty et al., 2017).

Psychologists need to work across microsystems –both those identified in Figure 1 (neighborhoods, schools, families) and others (e.g., healthcare, juvenile justice, child welfare). Through the Missouri Prevention Center, two multi-disciplinary teams including psychologists used a local sales tax to fund and implement psychosocial screening in schools and offer evidence-based supports and case management at no cost (Herman et al., 2019). A team of psychologists and court professionals in Arizona developed and implemented an intervention based in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for juvenile detention centers (O’Hara et al., 2019), to address need for mental health services and lower arrest and recidivism rates.

Developmental psychologists were integral in leading federal government efforts in early childhood education, including the HeadStart program (Zigler & Styfco, 2004). Yet immigrant children have had low enrollment rates in HeadStart despite need and eligibility (Gelatt et al., 2014). Research shows CIF are more likely to attend HeadStart when the center is located in their neighborhood (census tract) (Neidell & Waldfogel, 2009). Psychologists can share information with public school administrators and community organizations about the health impact of local and federal policies, and can advocate for more inclusive policies within all sectors that impact human development (Hardy et al., 2021; Turner et al., 2021).

“Work "Upstream" by Promoting Prevention and Early Intervention Strategies”

The second principle “Work ‘upstream’ by promoting prevention and early intervention strategies” refers to psychologists’ direct research and practice of evidence-based strategies for prevention and early intervention, as well as advocacy for systematic change to scale these strategies up, such as policies for universal screening, wellness checks, and integration of behavioral health in primary care. As reported by Fuligni and Tsai (2015), healthy adolescent development is linked to taking a flexible approach to family cultural norms and their role within the host country. This is supported by host nation actions that value cultural pluralism. Placing value on and accepting families’ cultures can assist in higher positive cultural adjustment, with less pressure to acclimate via ethnic identity expression (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2018).

Preventive mental health programs (Tier 1) can move upstream by beginning early in life. Randomized controlled trials of the Abecedarian Approach (Sparling et al., 2021) show that enriched caregiving (birth through 3 or 5 years), is linked to lower risky behaviors (suicidal ideation and attempts, smoking, alcohol use, marijuana use and risky sexual behavior) at age 18, and fewer depressive symptoms at age 21. Several universal (i.e., offered to all students) school prevention programs can buffer the negative effects of exposure to trauma and adversity, such as mindfulness instruction (Sibinga et al., 2016), resilience-focused interventions based in a cognitive behavioral therapy approach (Dray et al., 2017), and a comprehensive behavioral health model with universal socio-emotional learning curriculum and annual behavioral health screening (Battal et al., 2020). Universal studies do include CIF, such as work by Brown and colleagues (2018). Evidence shows some programs are dramatically more likely to be completed if offered in schools rather than clinical settings (e.g., 91% versus 15%; Jaycox et al., 2010).

Regarding early intervention (Tier 2), the National Academies of Medicine’s 2019 Report for Fostering Healthy Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Development in Children and Youth: A National Agenda (2019) outlined the need for research “to develop interventions that are culturally sensitive and tailored to meet the needs of subgroups of children known to be vulnerable, such as children from immigrant backgrounds (pg. 351).” One example is a comprehensive package of seven school-based services designed for immigrant students with trauma symptoms (Beehler et al., 2012). An evaluation in two school districts showed that greater quantities of trauma-focused CBT and supportive therapy increased functioning, and greater quantities of program coordination improved reduced PTSD symptoms (Beehler et al., 2012). Due to the uniqueness of immigrant-origin children’s needs, some school-based mental health services are not used by immigrant children unless they are created in a collaborative approach with communities (McNeely et al., 2020). McNeely and colleagues (2020) discuss ways to create a collaborative approach with psychologists, school personnel, and cultural brokers, that prioritizes family engagement, basic needs assistance, and facilitates acclamation to a new culture, as well as emotional and behavioral supports.

Addressing immigration-specific factors in mental health with a focus on community outreach is imperative for adequate mental health care (Williams et al., 2007). For instance, involving and increasing support for community health workers within minoritized populations (Agarwal et al., 2019) can serve as a potential buffer for serving immigrant children at risk.

Psychologists can also lead in the screening and identification of CIF in need of educational and social supports, community outreach, and health education to increase opportunities to engage in schools, alleviate social isolation, and receive preventive mental health services (Burbage & Walker, 2018). For example, 10.2% of children in public schools are English language Learners (ELLs) as of 2018 (National Center for Education Statistics, 2021). A third of these students are in grades 6-12, struggling with academic instruction that is not adapted to their unique circumstances (Ascenzi-Moreno & Seltzer, 2021). Studies suggest that bilingual professionals are needed for measurement design and reading assessment refinement to better capture emergent bilingual students’ reading abilities (Ascenzi-Moreno & Seltzer, 2021). Bilingual psychologists have had a positive impact on performing assessments among English Language Learners students (O’Bryon & Rogers, 2010). Conceptual frameworks have described effective integration of mental health services using psychologists and psychiatric social workers building partnerships with academics for intervention design (Stein et al., 2002). Using bilingual and ethnically diverse psychiatric social workers, the Mental Health Immigrant Program (MHIP) was able to make several modifications to ensure student centered treatment (Stein et al., 2002).

Examining exposure to risks for CIF should be done in the context of resilience factors and resources, so that interventions can be appropriately targeted. Although measures of early childhood adversity predict poorer health at the population level, they are poor predictors of adverse changes in health at the individual level (Baldwin et al., 2021). Appropriately tailoring interventions to the needs of CIF requires not only assessment of risk exposure but also measurement of protective influences and resources present in the lives of specific children.

“Educate Psychologists and Community Partners on Population Health”

The third principle, “Educate psychologists and community partners on population health” includes training psychologists to work on multi-disciplinary and inter-professional teams oriented towards population-health science. Tensions arising from different theoretical orientations, methodological approaches, and language can imperil collaborative problem solving. Psychology’s epistemic domain assumptions frame “the problem” in individual terms, when the conditions creating the problems are socially and politically generated. The development of an equity lens approach for psychologists necessitates a wider range of approaches and perspectives (Proctor & Vu, 2019). Collaborations between psychology and the fields of sociology, anthropology, demography, economics, and social policy, among others, can advance our understanding of how intersecting societal systems (e.g., criminal justice, immigration, education) create and perpetuate health inequities, and solutions to address them. CIF perspectives should also be included in collaborations, through their full participation in identifying problems their communities face and making decisions about appropriate solutions. Complex problems, as identified in Figure 1, require a team-based approach that effectively integrates expertise in a broad range of areas with coordination across systems (Bisbey et al., 2019). In the last decade there have been a series of materials on how to achieve interdisciplinarity, including a special issue of American Psychologist (Proctor & Vu, 2019).

Research on housing policy and public health among immigrant families has been advanced by cross-disciplinary partnerships, such as law and public health (Benfer et al., 2021). Interdisciplinary teams at think tanks like the Urban Institute and PolicyLink have used data to design federal place-based policies which could advance racial equity and social mobility for youth (Turner et al., 2021). Implementation could change the way neighborhood built environment impacts child development and health (Hardy et al., 2021; Villanueva et al., 2016).

“Enlist a Diverse Array of Community Partners”

The fourth principle “Enlist a diverse array of community partners” includes community-based participatory research and action, and psychologists developing a range of relationships, for instance through opportunities to serve on local, state, or national coalitions or boards, community organizations, government entities, and global organizations. Psychologists’ role in addressing health inequities that impact immigrant communities would be strengthened through wider use of rigorous community-based participatory research (CBPR) methods (Woods-Jaeger et al., 2020). Despite strong evidence that CBPR is an effective method to address health inequities, it has been under-utilized in the field of psychology (Rodriguez Espinosa & Verney, 2021). Resources are available, such as the American Journal of Community Psychology’s special issue on CBPR research, featuring psychometrically validated measures of partnership processes and outcomes (Boursaw et al., 2021) and evidence of best practices based on research with over 400 partnerships. One best practice is higher levels of structural governance (e.g., community approvals, co-leadership, joint decision making) (Sanchez-Youngman et al., 2021). Empowerment, through gaining privileges or building a sense of community, appears to facilitate immigrants’ actions supporting direct external change to their contexts (Buckingham & Brodsky, 2021). This includes leadership and participation in community organizing to support changes to policies, institutions, and attitudes (Buckingham & Brodsky, 2021). Community-academic partnerships can also build capacity to conduct CBPR through experiential learning (Coombe et al., 2020), such as the Detroit Urban Research Center’s year-long training program in CBPR.

Psychologists have partnered with teachers, psychiatrists, youth organizations and other health professionals in the training and supervision of paraprofessionals (e.g., community health workers) to deliver preventive mental health interventions outside of the traditional settings. One example is the You’re Not Alone initiative (Ford-Paz et al., 2019), a multi-level intervention in which psychologists participated in advocacy (e.g., webinars, resource development and dissemination) and led trainings on culturally responsive and trauma-informed strategies for healthcare providers, paraprofessionals, and educators across public sectors. Psychologists could identify community supports to serve as referral sources to CIF, connecting them to opportunities and helping them navigate the nuance of complex institutional services. Spiritual leaders who were more knowledgeable about mental illness were more likely to act as facilitators to mental health services within Asian American communities (Yamada et al., 2012), suggesting the importance of collaborations with trusted community leaders. After African immigrant communities in Lowell, MA expressed needs about education around their mental health, the HEAAL Project was formed using a Community Advisory Board consisting of clinicians and community leaders (Oppenheim et al., 2019). Psychologists may improve mental health literacy in communities using trusted leaders as a bridge and facilitator to resources. Groups of psychologists could also partner with organizations creating mental health campaigns and toolkits for immigrant youth, like United We Dream, and spread awareness of their free online Immigration Relief Screening to determine eligibility for resources (United We Dream, 2021).

Psychological Research Findings Could Have More Impact If Conveyed Within Existing Relationships with Policy Makers

The APA’s February 2022 statement on “Psychology’s Role in Advancing Population Health” offers several concrete recommendations. These suggestions include doing work “upstream” from key problems, to prevent or diminish them, working within and across diverse populations, and ensuring psychologists and community partners understand the community health approach. APA would do well to make another concrete recommendation promoting the chances that psychological research matters to policy makers. Researchers often (and correctly) lament that their findings could inform better policy making but are not consulted in making policies. The biggest predictor of the impact of research on policies and practices is not the quality of the research, but rather the quality of the relationships with policymakers and practitioners (Gamoran, 2018). Use of psychologists’ research affecting CIF would increase if findings were conveyed within the context of strong, ongoing, relationships with institutions and policymakers and their staff whose decisions could be improved by the findings (Tseng, 2022).

Three types of supports could increase this. First, helping psychologists and other social scientists learn how to present their findings in ways that are accurate and can be understood by busy policy makers – and more often, their staffers – who have to have little time to read and must make decisions in real time. Organizations like the Frameworks Institute or the Scholar Strategy Network could be helpful. Second, APA could create rapid response publications (as sociology has done with Socius) that are peer reviewed, but fast tracked and open access, so they can weigh in on current debates. Third, universities and professional associations should increase their efforts to create ongoing relationships with policy makers and government offices or departments in their fields. It is not reasonable or sustainable to have individual researchers bearing the responsibility for cultivating these relationships. Examples of such ongoing relationships include the Houston Education Research Consortium (https://herc.rice.edu/) and the Research to Policy Collaboration (https://research2policy.org/).

Conclusion

Psychologists are well-positioned to change systems that contribute to health inequities for CIF. We argue that they can do so by learning and liaising to support immigrant youth and families in bringing their experiences to decision-making tables. Our vision is for psychologists to be leaders in the training and supervision of a paraprofessional workforce, and collaborators in partnerships needed to advance access to upstream social resources to offer CIF a better future.

Public Significance Statement:

In this perspective article, the authors identify opportunities for psychologists to use an equity lens in their work with children in immigrant families (CIF), to tackle social and structural inequities that adversely affect CIF’s mental health outcomes. Psychologists can support health equity by leveraging their expertise to improve multidisciplinary collaboration across systems and enhance communication with researchers, policymakers, and community members to bridge across disciplines and link resources of diverse systems to better serve the needs of CIF.

Acknowledgements:

Lauren Cohen, BA assisted with the research and Sheri Lapatin Markle, MIA provided feedback on the initial draft.

Funding Source:

This study was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, Grant R01MD014737-02, and the National Institute of Mental Health, Grant R01MH117247. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the funders.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The Authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- Acevedo-Garcia D, Joshi PK, Ruskin E, Walters AN, & Sofer N (2021). Restoring An Inclusionary Safety Net For Children In Immigrant Families: A Review Of Three Social Policies. Health Affairs, 40(7), 1099–1107. 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Garcia D, Joshi PK, Ruskin E, Walters AN, Sofer N, & Guevara CA (2021). Including Children in Immigrant Families in Policy Approaches to Reduce Child Poverty. Academic Pediatrics, 21(8, Supplement), S117–S125. 10.1016/j.acap.2021.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Garcia D, Walters A, Shafer L, Wong E, & Joshi P (2022). A Policy Equity Analysis of the EITC: Fully Including Children in Immigrant Families and Hispanic Children in this Key Anti-poverty Program. Diversity Data Kids. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal S, Sripad P, Johnson C, Kirk K, Bellows B, Ana J, Blaser V, Kumar MB, Buchholz K, Casseus A, Chen N, Dini HSF, Deussom RH, Jacobstein D, Kintu R, Kureshy N, Meoli L, Otiso L, Pakenham-Walsh N, … Warren CE (2019). A conceptual framework for measuring community health workforce performance within primary health care systems. Human Resources for Health, 17(1), 86. 10.1186/s12960-019-0422-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2021). APA apologizes for longstanding contributions to systemic racism. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2021/10/apology-systemic-racism [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2022). Psychology’s Role in Advancing Population Health (pp. 1–5). https://www.apa.org/about/policy/population-health-statement.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Armenta A (2017). Protect, Serve, and Deport (1st ed.). University of California Press; JSTOR. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1w8h204 [Google Scholar]

- Asad AL, & Clair M (2018). Racialized legal status as a social determinant of health. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 19–28. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascenzi-Moreno L, & Seltzer K (2021). Always at the Bottom: Ideologies in Assessment of Emergent Bilinguals. Journal of Literacy Research, 53(4), 468–490. 10.1177/1086296X211052255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin JR, Caspi A, Meehan AJ, Ambler A, Arseneault L, Fisher HL, Harrington H, Matthews T, Odgers CL, Poulton R, Ramrakha S, Moffitt TE, & Danese A (2021). Population vs Individual Prediction of Poor Health From Results of Adverse Childhood Experiences Screening. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(4), 385–393. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batalova J, Hanna M, & Levesque C (2021). Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Battal J, Pearrow MM, & Kaye AJ (2020). Implementing a comprehensive behavioral health model for social, emotional, and behavioral development in an urban district: An applied study. Psychology in the Schools, 57(9), 1475–1491. 10.1002/pits.22420 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beehler S, Birman D, & Campbell R (2012). The Effectiveness of Cultural Adjustment and Trauma Services (CATS): Generating practice-based evidence on a comprehensive, school-based mental health intervention for immigrant youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(1–2), 155–168. 10.1007/s10464-011-9486-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benfer EA, Vlahov D, Long MY, Walker-Wells E, Pottenger JL, Gonsalves G, & Keene DE (2021). Eviction, Health Inequity, and the Spread of COVID-19: Housing Policy as a Primary Pandemic Mitigation Strategy. Journal of Urban Health : Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 98(1), 1–12. 10.1007/s11524-020-00502-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisbey TM, Reyes DL, Traylor AM, & Salas E (2019). Teams of psychologists helping teams: The evolution of the science of team training. American Psychologist, 74(3), 278–289. 10.1037/amp0000419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boursaw B, Oetzel JG, Dickson E, Thein TS, Sanchez-Youngman S, Peña J, Parker M, Magarati M, Littledeer L, Duran B, & Wallerstein N (2021). Scales of Practices and Outcomes for Community-Engaged Research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 67(3–4), 256–270. 10.1002/ajcp.12503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouza J, Camacho-Thompson D, & Carlo G (2018). The science is clear: Separating families has long-term damaging psychological and health consequences for children, families, and communities. Society for Research on Child Development. https://www.srcd.org/sites/default/files/resources/FINAL_The%20Science%20is%20Clear_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Brown CH, Brincks A, Huang S, Perrino T, Cruden G, Pantin H, Howe G, Young JF, Beardslee W, Montag S, & Sandler I (2018). Two-Year Impact of Prevention Programs on Adolescent Depression: An Integrative Data Analysis Approach. Prevention Science : The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 19, 74–94. 10.1007/s11121-016-0737-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham SL, & Brodsky AE (2021). Relative Privilege, Risk, and Sense of Community: Understanding Latinx Immigrants’ Empowerment and Resilience Processes Across the United States. American Journal of Community Psychology, 67(3–4), 364–379. 10.1002/ajcp.12486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budiman A, Tamir C, Mora L, & Noe-Bustamante L (2020, August 20). Immigrants in America: Key Charts and Facts. Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2020/08/20/facts-on-u-s-immigrants/ [Google Scholar]

- Burbage ML, & Walker DK (2018). A Call to Strengthen Mental Health Supports for Refugee Children and Youth. NAM Perspectives. 10.31478/201808a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes AG, & Menjívar C (2020). Legal Violence, Health, and Access to Care: Latina Immigrants in Rural and Urban Kansas. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 61(3), 307–323. 10.1177/0022146520945048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Trends. (2018). Immigrant Children. Child Trends. https://www.childtrends.org/indicators/immigrant-children [Google Scholar]

- Chu MT, Williams DR, Todd TJ, Coull BA, & Adamkiewicz G (2021). Social Determinants of Housing Quality for U.S. Immigrants: Intersections of Nativity, Race, and Socioeconomic Status. ISEE Conference Abstracts. 10.1289/isee.2021.O-LT-040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coombe CM, Schulz AJ, Brakefield-Caldwell W, Gray C, Guzman JR, Kieffer EC, Lewis T, Reyes AG, Rowe Z, & Israel BA (2020). Applying Experiential Action Learning Pedagogy to an Intensive Course to Enhance Capacity to Conduct Community-Based Participatory Research. Pedagogy in Health Promotion, 6(3), 168–182. 10.1177/2373379919885975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dray J, Bowman J, Campbell E, Freund M, Wolfenden L, Hodder RK, McElwaine K, Tremain D, Bartlem K, Bailey J, Small T, Palazzi K, Oldmeadow C, & Wiggers J (2017). Systematic Review of Universal Resilience-Focused Interventions Targeting Child and Adolescent Mental Health in the School Setting. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(10), 813–824. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.07.780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enriquez LE (2015). Multigenerational Punishment: Shared Experiences of Undocumented Immigration Status Within Mixed-Status Families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(4), 939–953. 10.1111/jomf.12196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eskenazi B, Fahey CA, Kogut K, Gunier R, Torres J, Gonzales NA, Holland N, & Deardorff J (2019). Association of Perceived Immigration Policy Vulnerability With Mental and Physical Health Among US-Born Latino Adolescents in California. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(8), 744–753. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Paz RE, Santiago CD, Coyne CA, Rivera C, Guo S, Rusch D, St Jean N, Hilado A, & Cicchetti C (2019). You’re not alone: A public health response to immigrant/refugee distress in the current sociopolitical context. Psychological Services, 17(S1), 128–138. 10.1037/ser0000381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, & Tsai KM (2015). Developmental flexibility in the age of globalization: Autonomy and identity development among immigrant adolescents. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 411–431. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamoran A (2018). The Future of Higher Education Is Social Impact. 10.48558/83VF-CJ48 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia A (2019). Legal Passing: Navigating Undocumented Life and Local Immigration Law. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gelatt J, Adams G, & Huerta S (2014). Supporting Immigrant Families’ Access to Prekindergarten (p. 37). The Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/22286/413026-Supporting-Immigrant-Families-Access-to-Prekindergarten.PDF [Google Scholar]

- Gelatt J, Capps R, & Fix M (2021). Nearly 3 Million U.S. Citizens and Legal Immigrants Initially Excluded under the CARES Act Are Covered under the December 2020 COVID-19 Stimulus (p. 6). Migration Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Hainmueller J, Lawrence D, Martén L, Black B, Figueroa L, Hotard M, Jiménez TR, Mendoza F, Rodriguez MI, Swartz JJ, & Laitin DD (2017). Protecting unauthorized immigrant mothers improves their children’s mental health. Science, 357(6355), 1041–1044. 10.1126/science.aan5893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen H, & Metzl JM (2019). Structural competency in mental health and medicine: A case-based approach to treating the social determinants of health. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy E, Joshi P, Leonardos M, & Acevedo-Garcia D (2021). Advancing Racial Equity through Neighborhood-informed Early Childhood Policies: A Research and Policy Review (pp. 1–55). Diversity Data Kids. https://www.diversitydatakids.org/sites/default/files/file/neighborhood-informed-early-childhood-policies_final_2021-09-27.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Herman KC, Reinke WM, Thompson AM, & Hawley KM (2019). The Missouri Prevention Center: A multidisciplinary approach to reducing the societal prevalence and burden of youth mental health problems. American Psychologist, 74(3), 315–328. 10.1037/amp0000433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández D, & Swope CB (2019). Housing as a Platform for Health and Equity: Evidence and Future Directions. American Journal of Public Health, 109(10), 1363–1366. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homeland Security. (2021). Court Ordered Reimplementation of the Migrant Protection Protocols. US Department of Homeland Security. https://www.dhs.gov/migrant-protection-protocols [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox LH, Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Walker DW, Langley AK, Gegenheimer KL, Scott M, & Schonlau M (2010). Children’s mental health care following Hurricane Katrina: A field trial of trauma-focused psychotherapies. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(2), 223–231. 10.1002/jts.20518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiester E, & Vasquez-Merino J (2021). A Virus Without Papers: Understanding COVID-19 and the Impact on Immigrant Communities. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 9(2), 80–93. 10.1177/23315024211019705 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linton JM, Green A, & Council on Community Pediatrics. (2019). Providing Care for Children in Immigrant Families. Pediatrics, 144(3), e20192077. 10.1542/peds.2019-2077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez WD, Kruger DJ, Delva J, Llanes M, Ledón C, Waller A, Harner M, Martinez R, Sanders L, Harner M, & Israel B (2017). Health Implications of an Immigration Raid: Findings from a Latino Community in the Midwestern United States. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 19(3), 702–708. 10.1007/s10903-016-0390-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly II TJ, Kiser L, Hill S, Briggs EC, Trunzo CP, Zafari Z, & Betancourt TS (2020). Unseen Costs: The Direct and Indirect Impact of U.S. Immigration Policies on Child and Adolescent Health and Well-Being. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(6), 873–881. 10.1002/jts.22576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely CA, Sprecher K, Bates-Fredi D, Price OA, & Allen CD (2020). Identifying Essential Components of School-Linked Mental Health Services for Refugee and Immigrant Children: A Comparative Case Study. The Journal of School Health, 90(1), 3–14. 10.1111/josh.12845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar C, & Abrego LJ (2012). Legal Violence: Immigration Law and the Lives of Central American Immigrants. 10.1086/663575 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar C, & Cervantes A (2016, November). The effects of parental undocumented status on families and children. CYF News. https://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/newsletter/2016/11/undocumented-status [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2015). The Integration of Immigrants into American Society (Waters MC & Pineau MG, Eds.). The National Academies Press. 10.17226/21746 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). Fostering Healthy Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Development in Children and Youth: A National Agenda. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 10.17226/25201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2021). English Language Learners in Public Schools. In The condition of education 2021 (pp. 1–4). https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/pdf/2021/cgf_508c.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Neidell M, & Waldfogel J (2009). Program participation of immigrant children: Evidence from the local availability of Head Start. Economics of Education Review, 28(6), 704–715. 10.1016/j.econedurev.2009.06.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Bryon EC, & Rogers MR (2010). Bilingual school psychologists’ assessment practices with English language learners: English Language Learners. Psychology in the Schools, 47(10), 1018–1034. 10.1002/pits.20521 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara KL, Duchschere JE, Shanholtz CE, Reznik SJ, Beck CJ, & Lawrence E (2019). Multidisciplinary partnership: Targeting aggression and mental health problems of adolescents in detention. American Psychologist, 74(3), 329–342. 10.1037/amp0000439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim CE, Axelrod K, Menyongai J, Chukwuezi B, Tam A, Henderson DC, & Borba CPC (2019). The HEAAL Project: Applying Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) Methodology in a Health and Mental Health Needs Assessment With an African Immigrant and Refugee Faith Community in Lowell, Massachusetts. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice: JPHMP, 25(1), E1–E6. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornelas IJ, Yamanis TJ, & Ruiz RA (2020). The Health of Undocumented Latinx Immigrants: What We Know and Future Directions. Annual Review of Public Health, 41(1), 289–308. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patler C, & Pirtle W (2018). From undocumented to lawfully present: Do changes to legal status impact psychological wellbeing among latino immigrant young adults? Social Science & Medicine (1982), 199, 39–48. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty J, Metzl JM, & Keeys MR (2017). Developing and Evaluating an Innovative Structural Competency Curriculum for Pre-Health Students. The Journal of Medical Humanities, 38(4), 459–471. 10.1007/s10912-017-9449-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pina AA, Polo AJ, & Huey SJ (2019). Evidence-based psychosocial interventions for ethnic minority youth: The 10-year update. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(2), 179–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineros-Leano M, Liechty JM, & Piedra LM (2017). Latino immigrants, depressive symptoms, and cognitive behavioral therapy: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 208, 567–576. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor RW, & Vu K-PL (2019). How psychologists help solve real-world problems in multidisciplinary research teams: Introduction to the special issue. American Psychologist, 74(3), 271. 10.1037/amp0000458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche KM, White RMB, Lambert SF, Schulenberg J, Calzada EJ, Kuperminc GP, & Little TD (2020). Association of Family Member Detention or Deportation With Latino or Latina Adolescents’ Later Risks of Suicidal Ideation, Alcohol Use, and Externalizing Problems. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(5), 1–9. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche KM, White RMB, Rivera MI, Safa MD, Newman D, & Falusi O (2021). Recent immigration actions and news and the adjustment of U.S. Latino/a adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 27(3), 447–459. 10.1037/cdp0000330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Espinosa P, & Verney SP (2021). The Underutilization of Community-based Participatory Research in Psychology: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 67(3–4), 312–326. 10.1002/ajcp.12469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez LA (2018). Segmented Paths? Mexican Generational Differences in the Transition to First-Time Homeownership in the United States. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 19(3), 737–755. 10.1007/s12134-018-0560-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Youngman S, Boursaw B, Oetzel J, Kastellic S, Devia C, Scarpetta M, Belone L, & Wallerstein N (2021). Structural Community Governance: Importance for Community-Academic Research Partnerships. American Journal of Community Psychology, 67(3–4), 271–283. 10.1002/ajcp.12505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangalang CC, Becerra D, Mitchell FM, Lechuga-Peña S, Lopez K, & Kim I (2019). Trauma, Post-Migration Stress, and Mental Health: A Comparative Analysis of Refugees and Immigrants in the United States. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 21(5), 909–919. 10.1007/s10903-018-0826-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Slopen N, & Williams DR (2021). Early Childhood Adversity, Toxic Stress, and the Impacts of Racism on the Foundations of Health. Annual Review of Public Health, 42(1), 115–134. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-101940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibinga EMS, Webb L, Ghazarian SR, & Ellen JM (2016). School-Based Mindfulness Instruction: An RCT. Pediatrics, 137(1). 10.1542/peds.2015-2532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RC, Patler C, Menjivar C, Massey D, Bachmeier J, Aranda E, Waters M, Bean F, Brown S, Abrego L, Amuedo-Dorantes C, Ortega F, & Hsin A (2019). 2019 Amici Curiae Brief of Empirical Scholars in Support of Respondents (Three Consolidated DACA Cases (18-587, 18-588, 18-589)). Supreme Court of the United States. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RC, Rayas AB, Flores D, Cabrera A, Barbosa GY, Weinstein K, Xique M, Bialeck M, & Torres E (2021). Disrupting the Traffic Stop–to-Deportation Pipeline: The New York State Greenlight Law’s Intent and Implementation. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 9(2), 94–110. 10.1177/23315024211013752 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sparling J, Ramey SL, & Ramey CT (2021). Mental Health and Social Development Effects of the Abecedarian Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 6997. 10.3390/ijerph18136997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein BD, Kataoka S, Jaycox LH, Wong M, Fink A, Escudero P, & Zaragoza C (2002). Theoretical basis and program design of a school-based mental health intervention for traumatized immigrant children: A collaborative research partnership. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 29(3), 318–326. 10.1007/BF02287371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco C, Motti-Stefanidi F, Marks A, & Katsiaficas D (2018). An integrative risk and resilience model for understanding the adaptation of immigrant-origin children and youth. The American Psychologist, 73(6), 781–796. 10.1037/amp0000265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Williams DR, Harvey-Mendoza E, Jahromi LB, & Updegraff KA (2014). Impact of Arizona’s SB 1070 Immigration Law on Utilization of Health Care and Public Assistance Among Mexican-Origin Adolescent Mothers and Their Mother Figures. American Journal of Public Health, 104(S1), S28–S34. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres JM, & Young M-ED (2016). A life-course perspective on legal status stratification and health. SSM - Population Health, 2, 141–148. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng V (2022). Research on research use: Building theory, empirical evidence, and a global field (pp. 1–20). William T. Grant Foundation. http://wtgrantfoundation.org/library/uploads/2022/03/Tseng_WTG-Digest-7.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Turner M, Williams J, Randall M, Velasco G, & Islam A (2021). Designing the next generation of federal place-based policy: Insights from past and ongoing programs. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104331/designing-the-next-generation-of-federal-place-based-policy_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- United We Dream. (2021). Toolkits and Resources: Resources to help you protect immigrants. https://unitedwedream.org/tools/toolkits/ [Google Scholar]

- US Customs and Border Protection. (2022). Southwest Land Border Encounters. https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/southwest-land-border-encounters [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva K, Badland H, Kvalsvig A, O’Connor M, Christian H, Woolcock G, Giles-Corti B, & Goldfeld S (2016). Can the Neighborhood Built Environment Make a Difference in Children’s Development? Building the Research Agenda to Create Evidence for Place-Based Children’s Policy. Academic Pediatrics, 16(1), 10–19. 10.1016/j.acap.2015.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Haile R, González HM, Neighbors H, Baser R, & Jackson JS (2007). The Mental Health of Black Caribbean Immigrants: Results from the National Survey of American Life. American Journal of Public Health, 97(1), 52–59. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Jaeger B, Cho B, & Briggs EC (2020). Training psychologists to address social determinants of mental health. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, Advance online publication. 10.1037/tep0000307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada A-M, Lee KK, & Kim MA (2012). Community Mental Health Allies: Referral Behavior Among Asian American Immigrant Christian Clergy. Community Mental Health Journal, 48(1), 107–113. 10.1007/s10597-011-9386-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, Kholoptseva J, & Suárez-Orozco C (2013). The Role of Public Policies and Community-Based Organizations in the Developmental Consequences of Parent Undocumented Status. Social Policy Report, 27(3), 1–24. 10.1002/j.2379-3988.2013.tb00076.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH, Brabeck KM, Heffron LC, Dreby J, Calzada EJ, Parra-Cardona JR, Dettlaff AJ, Heidbrink L, Perreira KM, & Yoshikawa H (2017). Charting Directions for Research on Immigrant Children Affected by Undocumented Status. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 39(4), 412–435. 10.1177/0739986317722971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigler E, & Styfco SJ (2004). The Head Start Debates. Brookes Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]